It is Valentine time again. In 2010 we mounted a small exhibition called The season for love in the Proscholium of the Bodleian Library. Last year, there was an international initiative on Twitter (#loveheritage) led by #AskArchivists to surface valentine collections, which resulted in our little online gallery of comic valentines.

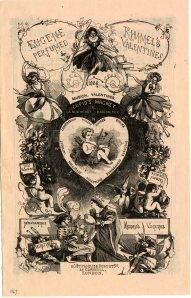

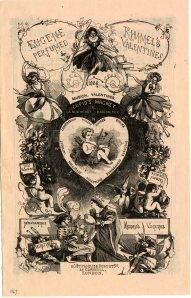

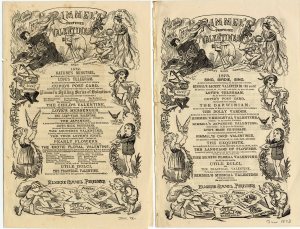

This year it is a great pleasure to collaborate with the National Valentine Collectors Association to highlight the valentines of Eugène Rimmel (1820–1887). Also online are the excellent special Rimmel issue of the Valentine Writer (newsletter of the National Valentine Collectors Association) by Nancy Rosin, and Malcolm Warrington’s beautiful online Rimmel exhibition.

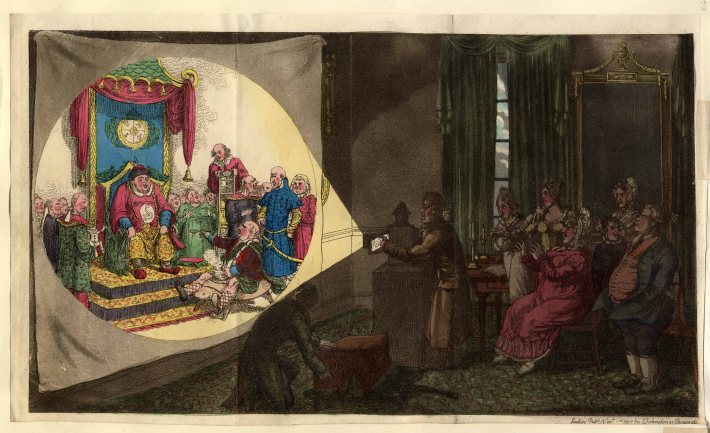

From Rimmel’s 1877 Topsy-Turvy pocket almanac. JJ: Beauty Parlour 4 (11b). (C) Bodleian Library & ProQuest

Images: all images are from the John Johnson Collection (JJ) and are copyright Bodleian Library, University of Oxford (and, where indicated) ProQuest. Click to see the large images, but do not reproduce any images without permission.

Rimmel in the John Johnson Collection

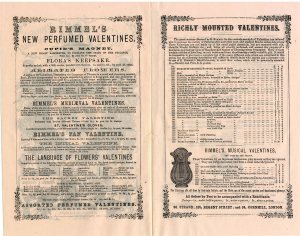

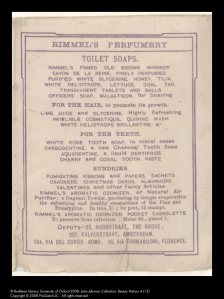

While we have 20 boxes and several albums of valentines in the John Johnson Collection, there are very few Rimmel valentines. However, we hold a wealth of ephemera relating to the varied activities of the firm. Advertisements for perfumes, table fountains, disinfectors, soaps, Christmas novelties, Easter eggs, fans, etc, are outside the scope of this blog, but much of this material has been digitised as part of ProQuest’s The John Johnson Collection: an archive of printed ephemera (freely available in the UK through FE, HE, public libraries and schools, and by institutional subscription elsewhere). I will explore here valentine-related advertising and, more widely, Rimmel’s relationship with the Theatre, whose programmes he used extensively to advertise his valentines and other seasonal merchandise.

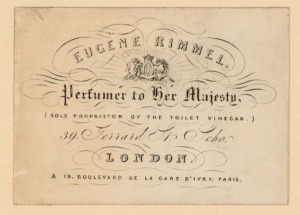

Trade card for Eugène Rimmel [1847-1857]. JJ: Trade Cards 5 (33). (C) Bodleian Library & ProQuest

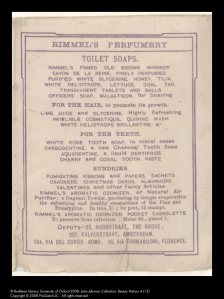

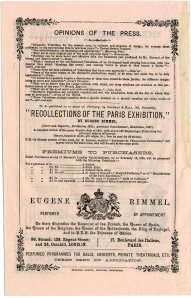

Eugène Rimmel (1820–1887) came to England from France and, with his father, established a perfumery business in London in 1834. From 1847 to 1857, he was in Gerrard St, Soho, with a branch in Paris at 19 boulevard de la Gare d’Ivry (now boulevard Vincent Auriol) in the 13th arrondissement. His claim to fame was as ‘sole proprietor of the toilet vinegar’ (an aromatic vinegar used as an emollient). He already enjoyed the Queen’s patronage.

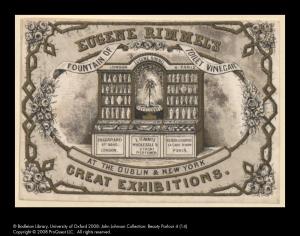

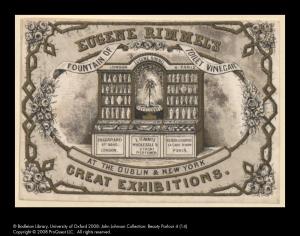

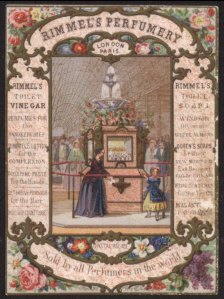

At the Great Exhibition of 1851, Rimmel attracted much attention for his ‘Great Exhibition Bouquet’ and his Perfume Fountain, which was also used in the Exhibition of Art and Art-Industry in Dublin (1853) and the New York Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations (1853–1854).

Eugene Rimmel advertisement, showing the Fountain of Toilet Vinegar. JJ: Beauty Parlour 4 (14) (C) Bodleian Library & ProQuest

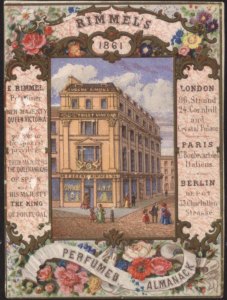

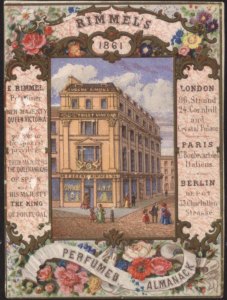

Rimmel’s 1861 perfumed almanack, showing his premises at 96 Strand. JJ Beauty Parlour 4 (1*a) (C) Bodleian Library & ProQuest

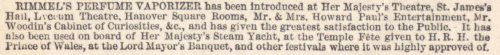

By 1861, Rimmel had premises at 96 Strand, 24 Cornhill and the Crystal Palace, Sydenham. In Paris, he was now in the more fashionable boulevard des Italiens (one of the grands boulevards) and there was another branch in Berlin. Rimmel’s royal patrons now included Queen Victoria, the King and Queen of Spain and the King of Portugal. He was ‘inventor and patentee of the perfume vaporizer, for balls, soirées, theatres, etc.’

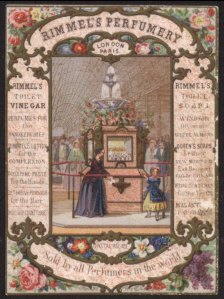

Rimmel’s 1861 perfumed almanack, showing the perfume fountain

Detail from a Vaporizer advertisement of 1862, listing the prestigious venues in which Rimmel’s vaporizer was used. JJ: Soap 1 (23) (C) Bodleian Library & ProQuest

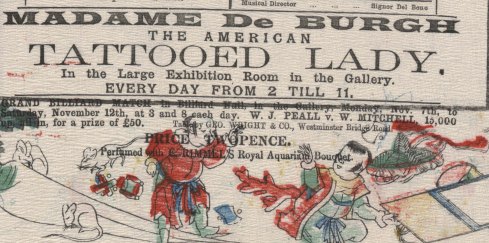

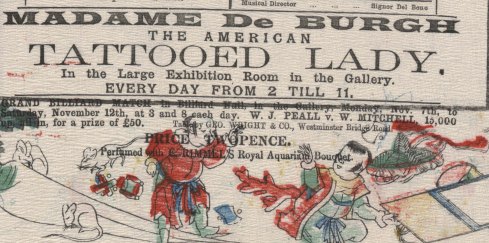

Rimmel used perfume imaginatively, to scent sachet valentines and theatre and concert programmes, including the fine Japanese programmes of the Royal Aquarium (detail below), which were perfumed with E. Rimmel’s Royal Aquarium Bouquet .

Imprint of Royal Aquarium programme, 12 November 1887. JJ: Entertainments folder 13 (7) (C) Bodleian Library & ProQuest

At the Haymarket in 1889, Rimmel’s Perdita Bouquet, dedicated to the famous actress Mary Anderson, and other perfumes were sold at the bars.

The Rimmel publicity machine was impressive. We have programmes in the John Johnson Collection from The Adelphi, Avenue Theatre, Canterbury Theatre of Varieties, Covent Garden, Drury Lane, Queen’s Theatre, Royal Alhambra Palace, Royal Aquarium, Royal Globe and Royalty theatres that proclaim they are perfumed by Rimmel. Undoubtedly, there were others. It is likely that the programmes (for a far wider range of theatres) that carry his advertisements or which are embossed ‘Rimmel’ were also perfumed. Where there is no statement to that effect we cannot be sure, and the perfume itself has of course long since evaporated!

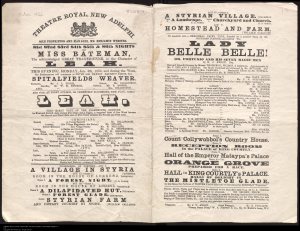

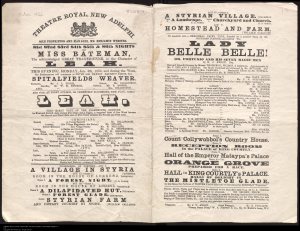

Playbill. Theatre Royal, New Adelphi, 29 February 1864. JJ London Playbills Adelphi box 1 (17)

(C) Bodleian Library & ProQuest

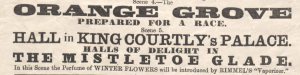

Rimmel’s perfumes were also integrated into his productions, such as Evanion’s An evening of illusions [c. 1871] and at the Theatre Royal, New Adelphi in February 1864 (left and below)

Detail from New Adelphi playbill

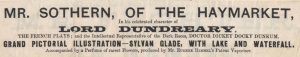

and at W.S. Woodin’s Cabinet of Curiosities.

Detail from W.S. Woodin Cabinet of curiosities playbill, [1861?] JJ Entertainments folder 5 (25) (C) Bodleian Library & ProQuest

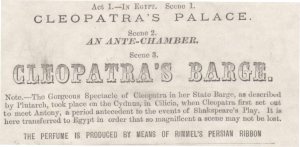

Detail from Drury Lane programme, 25 Oct 1873 for Anthony & Cleopatra. JJ London Playbills Drury Lane box 2 (4) (C) Bodleian Library & ProQuest

For Antony & Cleopatra at Drury Lane, a ‘Persian ribbon’ was used to scent the scene

![valentine advertising from Astley's programme, Boxing Night [1869]](https://johnjohnsoncollectionnowandthen.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/johnson10-bmsfor-blog-0003-0.jpg?w=190&h=300)

Back page of Astley’s programme, Boxing Night, [1869]. JJ London Playbills Apollo – Astley’s (69) (C) Bodleian Library & ProQuest

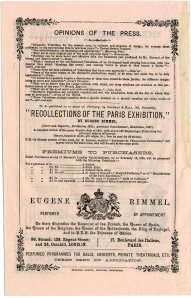

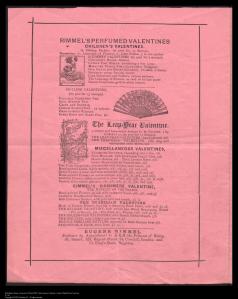

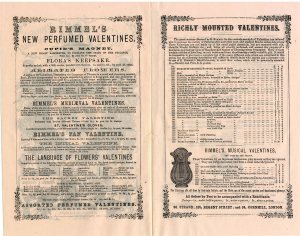

The advantage of theatre programmes and playbills was that they were printed frequently, sometimes daily. They were, therefore, ideal vehicles for seasonal advertising. In our holdings are programmes advertising valentines from 1869 to 1873, and for 1875 to 1880, 1885 and 1887.

Advertisement from 1879 Drury Lane programme. JJ: London Playbills Drury Lane box 2 (14) (C) Bodleian Library & ProQuest

This 1879 advertisement on the back page of a Drury Lane programme for The lost letter and Blue Beard shows that valentines were marketed for children. Rimmel used his countrymen Jules Chéret (more famous for his posters) and Faustin as designers of valentines.

Chéret ran a lithographic printing firm in the rue Brunel in Paris and many of Rimmel’s lithographed advertisements and almanacs carry his imprint.

Detail from back cover of Rimmel almanac, 1874. JJ: Beauty Parlour 4 (9b)

(C) Bodleian Library & ProQuest

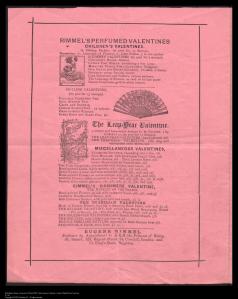

Although the annual almanacs were beautifully chromolithographed. the advertising pages (which sometimes refer to valentines) were usually modest.

- Advertising page from Rimmel’s comic almanac pocket-book, 1886. JJ Beauty Parlour 4 (13) (C) Bodleian Library & ProQuest

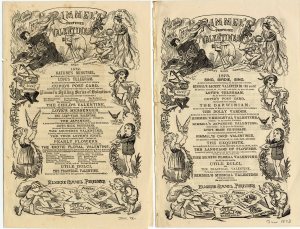

It was in his magazine inserts that Rimmel could indulge in more fanciful illustration, often again by Chéret. We have four-page valentine advertisements for 1868, 1869 and 1872-1874, variously printed by Chéret, Stephen Austin (Hertford) and Charles Terry (High Holborn).

Advertising leaflet for valentines, 1867. Cover (above), inside spread (below), back cover (right). JJ: Stationery 9. (C) Bodleian Library

Covers of two Rimmel advertising leaflets, 1872 and 1873, showing how Rimmel responded to the preoccupations of his time. JJ: Stationery 9 (C) Bodleian Library

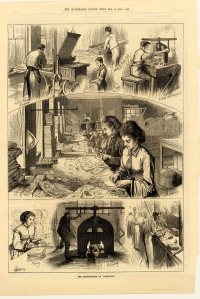

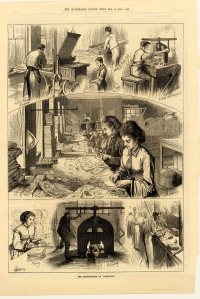

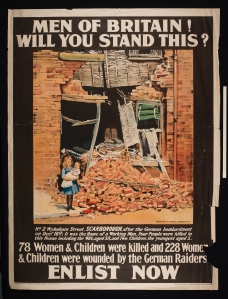

The Manufacture of Valentines. Illustrated London News 14 Feb 1787. JJ Valentines folder (C) Bodleian Library

The Rimmel empire continued to expand, with branches in Brighton, Florence, The Hague, Amsterdam, Brussels and Liège by 1874.

On 14 February 1874, The Illustrated London News showed and described the manufacture of valentines at the printing works of George Meek and the valentine workshop of Eugène Rimmel.

Just in time! In March 1875, a fire totally destroyed Beaufort House, the hub of the valentine side of the business. However, valentines continued to be produced, as evidenced by references to Rimmel’s ‘perfumed valentines, all novel and elegant, in great variety. Detailed list on application’ in a Rimmel advert on the back page of a Royal Princess’s Theatre programme for 28 June 1887, for example. However, references to Rimmel valentines are fewer and more modest. The otherwise rich online source for Rimmel research: 19th century UK periodicals (Gale, by subscription) has no results for advertising in magazines beyond 1877. However, as late as 1888, there are small advertisements for Rimmel valentines in newspapers, such as The Standard and The Morning Post which state that a detailed price list is available on application. Perhaps the fashion for valentines was declining, perhaps the firm slightly lost heart after the fire, or perhaps the perfume business was more lucrative. Or perhaps the public had come to associate Rimmel with valentines to such an extent that costly advertising was no longer necessary. The Standard for 12 February 1887 has a paragraph within its news pages: ‘The approach of St. Valentine’s-day is signalised, as usual, by the production of a number of graceful and ingenious valentines by Rimmel and Co., including expensive ones, and others which are at once tasteful and not too costly ‘. Whatever the case, the lace paper, tinsel, gauze, artificial flowers, feathers, scraps, etc. of Rimmel’s elaborate valentines gave pleasure to very many people in the 19th century and continue to do so to those who see them today.

![valentine advertising from Astley's programme, Boxing Night [1869]](https://johnjohnsoncollectionnowandthen.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/johnson10-bmsfor-blog-0003-0.jpg?w=190&h=300)